Crash course on Domain-Driven Design

- Intro

- Organization aspect

- Tactical developer patterns

- Overall structure

- Building RESTful interfaces

- Outro

Intro

A goal of this write-up is to introduce the main tools of domain-driven design to new developers so they can pick up the approach quickly.

There are two big parts of the domain-driven design: organizational (arguably more important) and tactical patterns for developers.

This will focus on the latter as for junior and mid-level developers the techniques mentioned here can take the quality of their code to the next level. I would also argue that the developers can become substantially more productive if they do DDD.

This post should be considered as a short intro and serious practitioners will want to read the following books:

- Domain-Driven Design: Tackling Complexity in the Heart of Software by Eric Evans

- Domain Driven Design Distilled by Vaughn Vernon

- Implementing Domain Driven Design by Vaughn Vernon

The “blue book” is a must-read for all level engineers if they haven’t done so. The “red book” would be more appropriate for architect-level contributors. Finally, the distilled version is useful as a refresher or as a review for more recent trends (like event sourcing).

Note: I’ll jump between different languages in my examples just to show that these concepts don’t apply to some language in particular but as a more general system.

Organization aspect

Let’s start with the organizational part as it’s quite important but I’ll keep it short as the focus of this post is to cover the technical bits. There are three main tools to be aware of:

Ubiquitous language

It’s a way to ensure that everybody is speaking the same language. Developers, project managers, and domain experts. Create and define all terms on some wiki page so when somebody writes a class “Post” you know what it means exactly and that it isn’t a “Blog” or something else.

Helps immensely to get everybody on the same page.

Bounded context

It’s a description of the scope for what the team is responsible for. Which parts of programs, features, or functionality some team will cover.

Context Map

This is useful for team leads and managers - it shows how different bounded contexts are connected and the connection interfaces (HTTP Rest Interface, Shared Database, etc) are defined.

Great to understand the structure and responsibilities of bigger systems.

Tactical developer patterns

The tactical patterns can make life a lot easier by shaping the software structure in such a way that it is easier to understand and maintain.

It helps to create a better distinction between infrastructure and domain code.

Quite often developers have a lot of trouble separating the core of the business code from something that’s shaped by the environment they are coding in. The first one delivers business value, while the second one enables the delivery of it. Distilling the first parts leads to easier maintenance and opens new paths for code re-use and generalization.

Entities

An Entity is an object (or a class) that has an identity. As soon as you see an ID field on the object it’s a strong sign it’s an entity.

For example,

class Post {

id: UUID;

title: String;

content: Text;

}

A note on entity IDs

There is no need for you to use database-assigned IDs. Sometimes they are convenient and useful and sometimes they can get in a way.

These days I am more of a fan of random UUIDs. And I am even a bigger fan of random UUIDs that are monotonically sorted by their timestamp or Universally Unique Lexicographically Sortable Identifiers (ULID). Examples:

These new ULIDs have a few nice properties:

- Creation timestamp is integrated within the ID itself

- You can sort them by bytes and get the same order as by timestamp - this makes range queries easy and efficient

- There is no need to do centralized locking to generate an ID - a client can generate an ID by itself.

- The IDs are impossible to guess (“oh, my order ID is 123, so let’s try entering in URL 122 to see if I can access data from some other customer”)

- The database doesn’t need to support “AUTOINCREMENT UNIQUE etc” column types

Value Objects

A Value object is a simple class that contains the information but isn’t necessarily distinguishable by some identifier.

class Weather {

raining: bool;

temperature: number;

measurementTime: Date;

}

Even if you decide to save this object in the database for some time series logging/analysis purposes

and you add some _id field it’s still a value object - the identity

of this piece of data doesn’t matter.

Factory

A factory pattern is just a standard pattern that’s used to create entities and value objects if the creation of such objects is a complex process. Don’t use it if you don’t need it, but it should be ready in your toolbox.

A good use of factories can ensure that even the most complex entities can be created in a simple and intuitive way.

Let’s take a look at the example, where we store Post objects that contain Weather information right

at the time when the Post was created:

class WeatherService {

function getCurrentWeather(): Weather {

return ...;

}

}

class Post {

id: UUID;

title: String;

content: Text;

currentWeather: Weather;

}

class PostFactory {

weatherService: WeatherService;

function create(title: String): Post {

return Post(

randomUUID(),

title,

"",

this.weatherService.getCurrentWeather()

)

}

}

However, if a simple constructor use is enough, just please use that. There is no need to make things more complicated than necessary.

Also, using factories inside repositories (later) is something that’s better avoided.

Aggregates & Aggregate Root

Aggregates are extremely important to understand and this is simpler said than done.

First of all, an aggregate is an Entity. Aggregates are about consistency and correctness of the state so when we say that some entity is an aggregate it means that there are some state consistency guarantees. I think it would be great to start with a few rules for aggregates:

- At any point in time, the whole state of an aggregate is valid

- Two instances of different aggregates are independant and there are no consistency guarantees

- Aggregate is loaded and saved via aggregate root

- The state of an aggregate is changed via aggregate root

- No object-reference links are allowed between entities from different aggregate roots - only linking by Identity (ID) is allowed.

At this point, we should clarify what’s an aggregate root. It’s an entry point to the aggregate (Entity) object. One aggregate can contain other entities so their state consistency can be guaranteed via their common aggregate root.

Consistency

A quick example with a case where the business rules are guaranteed at User aggregate:

class Address {

country: Country;

address: String;

}

class PaymentDetails {

country: Country;

providerPaymentUrl: URL;

}

/**

* Payment country and address country should always be matching due to our business

* requirements

*/

class User {

address: Address;

paymentDetails: PaymentDetails;

function updateAddress(newAddress: Address) {

/* once the new address is set, we invalidate payment details */

this.address = newAddress;

this.paymentDetails = null;

}

function addPaymentProvider(details: PaymentDetails) {

/* payment provider can only come from that country where the user is from */

if (details.country != this.address.country) {

throw new Exception("Payment provider country does not match user address");

}

this.paymentDetails = details;

}

}

Using the User interface we can guarantee the validity of the object’s state but only within that scope.

Domain-driven design abandons the idea of multi-aggregate consistency as it is often impossible to ensure

within distributed and horizontally-scaled applications.

If you need multi-aggregate consistency, you should rethink your approach to ensure that the most important guarantees are enforced at the aggregate level.

Entity Linking

Object-Relational Mapping (ORM) often does a horrible job linking different entities by offering lots of behind-the-scenes magic that usually leads to extremely complicated maintenance and all sorts of N+1 problems.

Domain-driven design just solves this problem in a simple way - no linking is allowed between two different aggregate roots.

This isn’t allowed:

class User {

id: UUID;

name: String;

invitingUser: User;

friends: List<User>;

}

but this is fine

class User {

id: UUID;

name: String;

invitingUserId: UUID;

friends: List<UUID>;

}

OR!!, you can actually keep the actual object as a “copy” like here

class User {

id: UUID;

name: String;

invitingUserSnapshot: User;

}

but then you have to be clear in your API design and docs that you should still be using

invitingUserSnapshop.id to look up the current version of the user and invitingUserSnapshot

was used just for historical safekeeping purposes.

Repository

A Repository is one of the main interfaces that connects your domain classes and infrastructure - it abstracts away all the aggregate (root) persistence details.

I am a big fan of how Spring Data has implemented its interfaces and I recommend the same naming style guide for all the systems I am building:

class UserRepository:

...

def save(self, user: User) -> User: ...

def save_all(self, users: list[User]) -> list[User]: ...

def find_one_by_id(self, id: uuid) -> User: ...

def find_one_by_email(self, email: str) -> User: ...

def exists(self, id: uuid) -> bool: ...

def find_all(self, ) -> Iterable[User]: ...

def find_all_by_name(self, name: str) -> Iterable[User]: ...

def find_all_by(self, email: str, name: str) -> Iterable[User]: ...

def delete(self, id: uuid): ...

I think you can see the pattern:

- simple and clearly named commands and queries

- whenever you can, you return the domain object itself

- it should (almost) always return the aggregate root so the consistency is guaranteed

- you should only save the entity at the aggregate root level

The technical details of how is that implemented are quite irrelevant as long as it works and you have integration tests to prove that.

More experienced developers will even realize that you could implement extremely simple persistence layers via this pattern just by using key-value stores that support range queries. Redis could be your next database of choice if you are tired of fighting your usual ORM.

Services

Service is like an entry point to some business process. If it’s not clear how to kick off some business-related commands/processes then it should probably go to the Service.

Please do not mistake services with Transactional Script which could quickly lead to an anemic domain model.

In most cases services are going to be quite simple and they are going to do a mix of the following:

- they will be called from HTTP API

- they will call other Services that they depend on

- they will load and save entities/aggregates with the help of Repositories

- manage the flow of the business process

A service could look something like this

class OrderService {

@Inject

UserRepository userRepo;

@Inject

EmailService emailService;

@Inject

OrderRepository orderRepository;

@Inject

PaymentService paymentService;

void approve(Order newOrder) {

User user = userRepo.findOneById(newOrder.getUserId());

if (!user.hasPaymentDetails()) {

throw new NoValidPaymentMethod();

}

try {

Order paidOrder = paymentService.chargeUser(user, order);

emailService.sendSuccessEmail(user, order);

orderRepository.save(paidOrder);

} catch (PaymentException e) {

Order failedPaymentOrder = order.addPaymentFailureDetails(e);

emailService.sendFailureEmail(user, order);

orderRepository.save(failedPaymentOrder);

}

}

}

As you can see, it’s responsible for the business process parts that do not naturally fall to either

of the domain classes like User and Order.

Overall structure

A few quick comments on the structure of the app itself.

Packages (Modules)

Package your code by feature . Create layer-based packages within the feature packages if needed. You might also need some sub-feature packages for bigger parts of the system so be on a lookout for that.

Just for the sake of god please do not do a layered design like people used to do in Java EE days.

The way you structure the code should follow the following rule - “there should be one reason for code to change”. The same is with code structure - if you go with the layered design you will be changing multiple packages at once by definition if some bigger feature change is introduced.

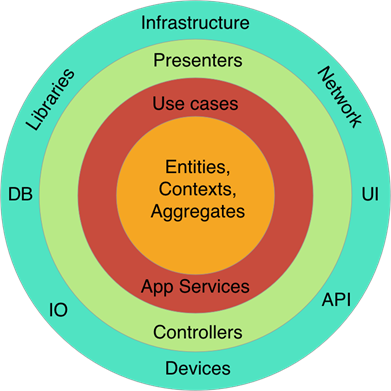

Infrastructure vs domain model

It’s quite useful to understand the conceptual separation between your domain model and infrastructure.

The domain model consists of:

- Aggregates

- Services

- Repositories

- Domain Events

The infrastructure is something like:

- MySQL database

- React frontend (and RESTful APIs to support it)

- etc

Conceptually, your domain model should be able to replace React frontend with CLI and MySQL database should be replaceable by simple csv files. The domain model should not change just because you’ve changed some technical implementation bits.

Of course, there is no need to go on and ensure that everything is replaceable at moments notice but use this as a mental excersice to have a clear separation to yourself.

Building RESTful interfaces

Matching RESTful interfaces with domain-driven design can be a tricky business.

There is a fundamental mismatch between the two. The RESTFul interface is about returning and updating the representation of the object and that’s often exposed as a CRUD-like interface via POST/GET/PUT/DELETE methods.

However, some of these actions might not be allowed via domain model rules and the current state of entities (like, you can’t update the list of order items or its state once the order is completed).

Quite often I end up doing something like this

class OrderRest:

def PUT(self, data):

new_order: Order = json_decode(data, Order)

# we don\t trust the state of the order object from the user so

# let's load it again

order = self.order_repo.find_one_by_id(id=new_order.id)

# in this method, we only allow order updates if it isn't completed yet

if order.status == OrderStatus.COMPLETED:

raise OrderCompletedException()

# we can now move to the new status

order.move_to_status(new_order.status)

# save it and return the new version from the repo

order = order_repo.save(order)

# serialize back to JSON and return it

return json_encode(order)

sometimes things are a bit easier if you can extract the sub-controller for the sub-resource for that domain object like Items within the Order:

class OrderItemsRest:

# add new items

def POST(self, order_id, data):

# Why we are always passing the whole item (or any other domain object) if we just need an id?

# On RESTful interfaces you re-use the representation that you retrieved somewhere else.

# In this case, Item might have been retrieved from GET /category/123/items call which

# returns object of content-type: application/vnd.Items+json

# while this POST call also consumes content-type: application/vnd.Items+json

item: Item = json_decode(data, Item)

# we don\t trust the state of the order object from the user so

# let's load it again

item = self.items_repo.find_one_by_id(id=item.id)

order = self.order_repo.find_one_by_id(id=order_id)

# in case we are doing immutable updates, we should assign it back to order variable

order = order.add_item(item)

order = order_repo.save(order)

return json_encode(order)

# remove existing items

def DELETE(self, order_id, item_id):

# here we get order_id and item_id because the call was

# DELETE /orders/223/items/343 and no body was provided within the request

order = self.order_repo.find_one_by_id(id=order_id)

order = order.remove_item(item_id=item_id)

order = order_repo.save(order)

return http(status=204)

Overall, it’s not really that difficult to do mapping between RESTful interface and domain model it’s not the best match either. I imagine that RPC calls would feel a lot more natural but our frontend developers and other API consumers wouldn’t be too happy about that :).

One acceptable alternative is to adopt Event Sourcing and use Commands to make these updates which can be a lot more natural way of connecting an HTTP-based REST-like interface with the domain model. However, this is a topic for another day.

Outro

I hope this crash course on domain-driven design patterns for developers is useful. There is more stuff that could be useful for developers but at this point, I would just recommend reading the blue book. You will find out about:

- anti-corruption layer

- shared-kernel

- and other quite useful bits

Overall, I think that these approaches can help shape your programs to be more business oriented while avoiding the pollution of all the infrastructure that often trashes the readability and understandability of the code.

Adopting domain-driven design takes a lot of practice so just take your time and keep trying.